Fleischner 2017 guideline for pulmonary nodules

by Onno Mets and Robin Smithuis

the Academical Medical Centre, Amsterdam and the Alrijne Hospital, Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Pulmonary nodules are frequently encountered incidentally on chest CT.

The

role of the radiologist is to separate between benign and possibly malignant

lesions, and advise on follow-up imaging or additional invasive imaging

techniques.

This article summarizes the basics of indeterminate pulmonary nodules, and presents the newest management recommendations of the Fleischner Society.

Introduction

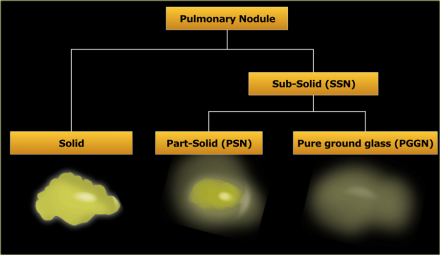

Pulmonary nodules can be divided into solid lesions and subsolid lesions,

which can be further subdivided into part-solid and pure ground glass

nodules.

Here some definitions:

- Subsolid nodule (SSN)

A pulmonary nodule with at least partial groundglass appearance - Groundglass

Opacification with a higher density than the surrounding tissue, not obscuring underlying bronchovascular structures

Fleischner Guideline 2017

Introduction

In 2017 the updated Fleischner Society guideline was published[1].

These

replace the recommendations for solid (2005) [2] and subsolid pulmonary nodules

(2013) [3].

These new guidelines should reduce the number of unnecessary

follow-up examinations and provide clear management decisions.

Nodule characterization should be performed on thin-slice CT images ≤1.5 mm, since a small solid nodule may appear to have groundglass density on a thick slice due to partial-volume effect.

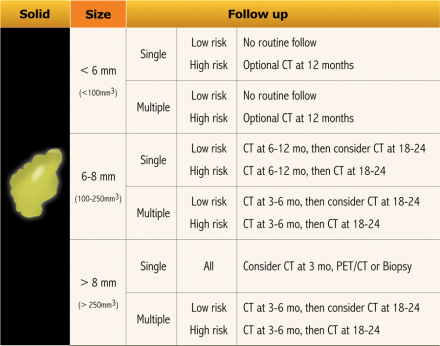

Solid nodules

Solid pulmonary nodules can represent various etiologies:

- benign granulomas

- focal scar

- intrapulmonary lymph nodes

- primary malignancies

- metastatic disease.

Perifissural nodules are a separate entity, since they usually represent

intrapulmonary lymph nodes, which are benign and need no follow up.

They are

discussed in the last

chapter.

In another article we presented some features that can help

to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions (click

here)

Unfortunately, there is considerable overlap and often no

definitive answer can be given based on imaging morphology.

Follow-up is

therefore a commonly used strategy.

Subsolid nodules

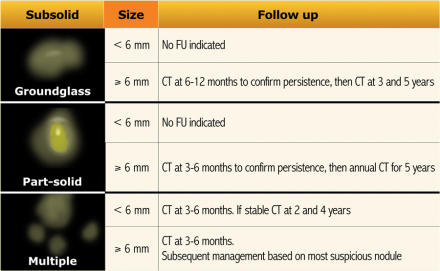

Most subsolid nodules are transient and the result of infection or

hemorrhage.

However, persistent subsolid nodules often represent pathology in

the adenocarcinomatous spectrum.

No reliable distinction can be made radiologically, although studies suggest

that larger size and a solid component are associated with more invasive

behaviour.

Compared to solid lesions, persistent subsolid nodules have a much

slower growth rate, but carry a much higher risk of malignancy.

In a study by

Henschke et al., part-solid nodules were malignant in 63%, pure groundglass SSNs

in 18% and solid nodules only in 7% [4].

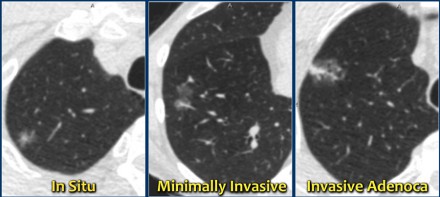

Subsolid nodules in the adenocarcinomatous spectrum were formerly known as

bronchoalveolar carcinoma or BAC.

This terminology should no longer be

used.

A new pathology-based classification for adenocarcinoma was introduced in 2011 and this current classification makes distinction between:

- Adenocacinoma in situ.

- Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma.

- Invasive adenocarcinoma.

Transient subsolid nodules usually represent infection or alveolar

hemorrhage.

To differentiate between transient or persistent subsolid nodules

a follow-up CT should be obtained.

Previously, it was recommended to repeat

imaging after 3 months, however, this interval has been increased to 12

months.

Because of the slower growth rate, the total follow-up period for

persistent subsolid nodules has been increased to 5 years.

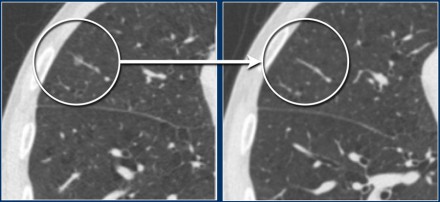

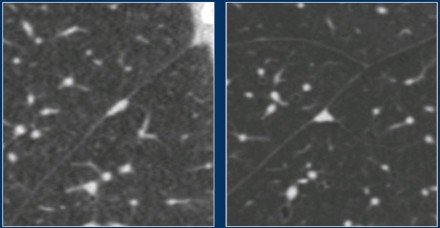

The images show a 7 mm pure groundglass subsolid nodule in the right upper

lobe.

On follow-up CT this proved to be a transient subsolid

nodule.

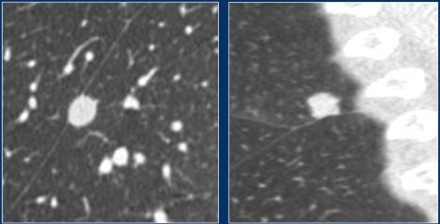

These images show a pure groundglass subsolid nodule in the right lower

lobe.

This lesion demonstrated growth in a two year interval and proved to be

malignant after resection.

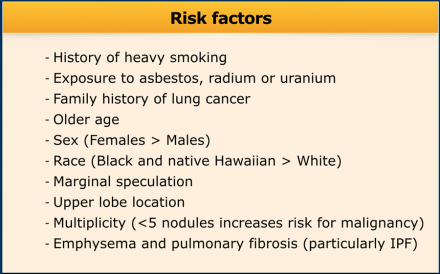

Risk factors

Defining high- or low-risk is currently more difficult than it was in the old

guideline.

Previously a high-risk subject was identified based on a history

of heavy smoking, history of lung cancer in a first-degree relative or exposure

to asbestos, radon or uranium.

Now, it is aimed for to separate high-risk lesions from low-risk ones by considering more parameters than subject characteristics alone (See Table).

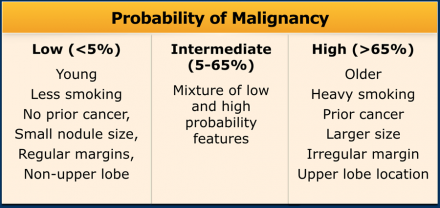

Since these risk factors are numerous and have different effects on the malignancy risk, it is proposed to assess final risk categories concerning the probability of malignancy [8](Table).

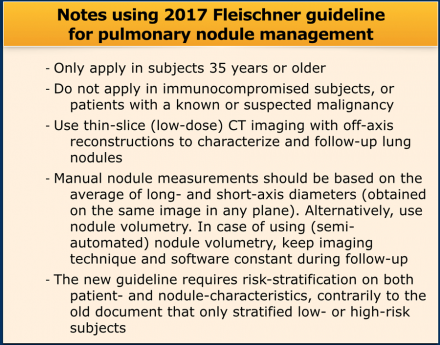

Notes

The guideline recommends follow-up for nodules with an estimated lung cancer risk of around 1% or greater, which is an arbitrary cut-off.

The likelihood of malignancy is different for an incidentally found pulmonary

nodule in the lower lobe of a relatively young patient compared to a nodule in

the upper lobe of a high-risk heavy smoker, or in a patient with a known or

suspected malignancy.

For this reason the Fleischner guideline for the

management of pulmonary nodules separates high- and low-risk, and does not apply

to subjects younger than 35 years, immunocompromised patients or patients with

cancer [1].

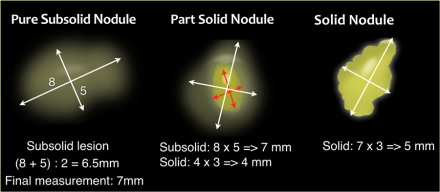

Pulmonary Nodule Measurements

In the Fleischner guidelines nodule dimensions can be obtained using either

2D caliper measurements or 3D nodule volumetry.

Manual 2D caliper

measurements should be based on the average of the long- and short-axis

diameters of the nodule.

These should be obtained on the same transverse,

coronal or sagittal reconstructed image, whichever plane reveals the greatest

dimensions [1].

This is new compared to the prior guideline, in which

dimensions were averaged diameters in the axial plane only [2].

Manual 2D

caliper measurements should be rounded to the nearest whole millimeter.

In part-solid subsolid nodules both the total nodule as well as the solid

component dimensions should be measured separately, both using the

abovementioned averaging technique.

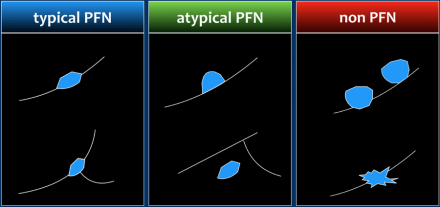

Perifissural nodules

Perifissural nodules are a separate entity, and likely represent

intrapulmonary lymph nodes.

Morphologically these are solid, homogeneous

nodules with a smooth margin, and are oval or rounded, lentiform or triangular

in shape.

Their location is within 15 mm of the fissure or the pleura. They

may or may not have contact with an interlobar septum.

The latter

differentiates between a typical and atypical PFN (see Figure).

PFNs can show

significant growth rates on serial imaging, sometimes comparable to malignant

nodules.

This is not a typical sign of malignancy, but merely a result of

their presumed lymphatic origin.

In screening setting it has been shown that none of the 919 typical and

atypical PFNs were found to be malignant in a 5.5 year follow-up [5].

This

confirmed prior results of Ahn et al. [6].

It is assumed that this benign

etiology can be extrapolated to clinical subjects, which is supported by yet

unpublished data in routine-care clinical CT imaging [7].

The currently available guidelines recommend that when small nodules have a perifissural or other juxtapleural location and a morphology consistent with an intrapulmonary lymph node, follow-up CT is not recommended, even if the average dimension exceeds 6 mm.

Perifissurally located nodules that do not conform to the morphologic characteristics should be regarded as non-PFN nodules (Figure) and does require follow-up.